The postdoctoral fellow at the California Academy of Sciences shares her passion for the underappreciated Selenopidae spider family, and speaks to the difficult funding ecosystem that defines research opportunities in academia.

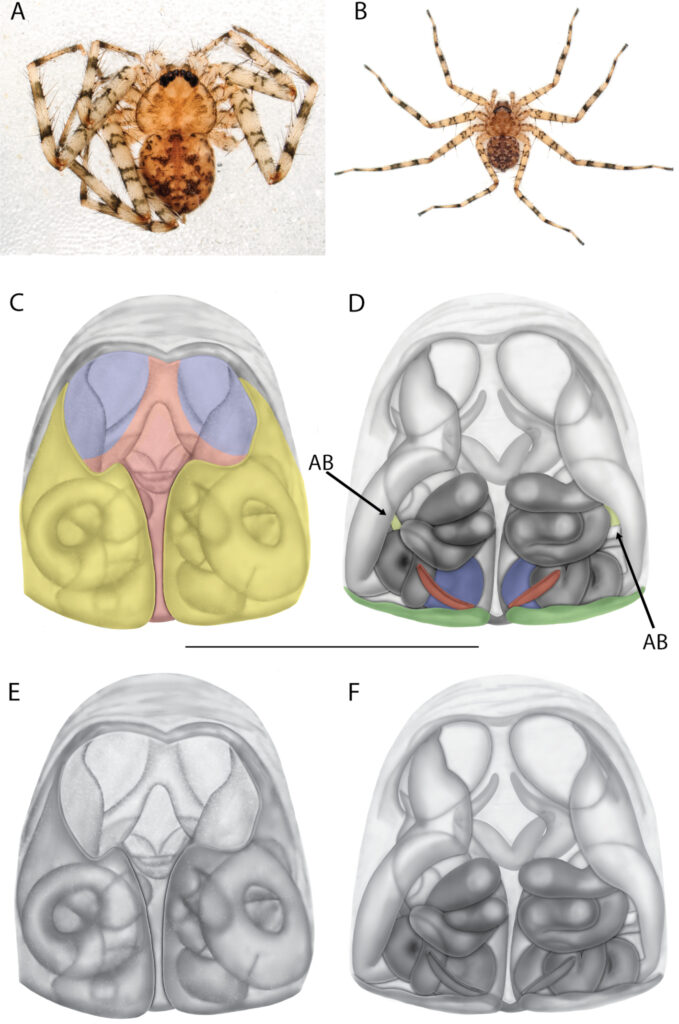

The Selenopidae spider family now encompasses over 280 species of spiders, thanks in part to the work of Dr. Crews. Throughout her career she has sought to describe new species of the ‘flatty’ spider family, exploring just about every facet of their biology – from mating behavior to biomechanics.

Your research focuses on so many different aspects of these Selenopidae or ‘flatty’ spiders, what do you like about flatties as opposed to other spiders?

I like them a lot more than other spiders. They don’t build webs. They’re the fastest turning animal on earth. They’re very flat. When I first started working on them, they were considered a small spider family, but I’ve described maybe 75 or 100 species. Meanwhile, other people have been describing them too, and so my guess is there’s probably a whole lot more.

I think that they were sort of overlooked because they are really fast and they are really flat. So if you’re up collecting, if you’re not collecting those specifically, you’re not gonna look for them and they’re gonna be hard to find. If you see one and you’re not good at catching them because you haven’t done it before, then you’re not gonna really worry about it if it’s not something you need, because you need to focus on your own research. So I think it’s just a matter of people not actually collecting them.

You have done all these different types of research on this one particular group. Is there one aspect that you find most interesting?

Well, I like describing species because I would like to say most arthropods are differentiated by their genitalia. There’s over 52,000 species of spiders, and then you have males and females, so thats 52,000 different kinds of genitalia. That’s just so much, you could never sit down and do all that, but it exists, there’s that much variation, and that’s really interesting to me.

I also like biomechanics because it was an accident how my friend Joe Spagna and I found it and we’re still working on a lot of aspects of it. My friend had an undergrad student, Karisa Quimby, that worked on leg loss, (sometimes legs just come off of spiders) and she did the same experiments we did, but looked at if they slowed down or missed their prey. They can get down to five legs before you have a problem.

Source: Crews SC (2023) But wait, there’s more! Descriptions of new species and undescribed sexes of flattie spiders (Araneae, Selenopidae, Karaops) from Australia. ZooKeys 1150: 1–189. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.1150.93760

Five out of eight?

Yeah if you have five, you’re still doing good, but lower than that, you start to taper off. There’s a lot of unknown aspects like that. They also have really big eyes, but we don’t know what they’re using them for. My friend Benji and I covered them up with dental silicone, which isn’t very easy to do, to put dental silicone on tiny spider eyes, but we did that and they were still able to do everything. We did the experiments in the dark and in the light, the way they catch prey probably has more to do with these innervated hairs on their legs, but they gotta be using their eyes for something. So I just like that aspect of it because there are just so many things that aren’t known about them.

That’s kind of another problem with academia. People want you to engage with the public and the public wants to know things like that. What did they do? What do they eat? But there’s never funding for things like natural history work or like observation work. Anybody who’s doing that is doing it on their own time or when they’re doing something else and that’s always kind of been annoying to me.

There’s so many unknowns for all spiders, but unknowns aren’t as impactful and exciting to fund research. The public wants to know about it, but academics don’t want you to do that. They don’t wanna give you money to do that. The government doesn’t wanna give you money to do that.

Can you speak to some of the difficulties of being a scientist in academia?

I never wanted to be an academic scientist and I’m not very good at it, because I’m not really competitive. I just wanna find my stuff and do my thing. And I like listening to other people’s talks but people get so wrapped up in their own ideas that they can’t ever listen to anyone else’s. Also, being young and being a woman, there’s just so many people that don’t acknowledge work I’ve done and they write papers and they don’t cite my work. I’ve been doing this for forever and people know I’ve been doing it, and so, it’s just kind of annoying. The stuff that we’ve been doing in the lab has been really good and they’re just kind of not great about it recently.

Trying to get money has always been difficult and it’s gotten more difficult through the years, and right now they might dissolve the National Science Foundation, so there might not be any more.

For younger scientists, could you speak to the role of mentorship in your career? You’ve also been an educator, have you been able to impart mentorship?

Well, I didn’t have very good mentors, so I learned pretty quickly what not to do. Some of them were just mean and terrible, and some of them were just like so hands off when you needed help. But if you’re in a big enough lab, you can sort of lean on the other students in there. You know, I’ve had some better ones that weren’t necessarily my supervisors. My boss here is really good, especially with education, like teaching me how to do more outreach.

I do also have students here. I have a masters student, and then I’m helping I’m on dissertation committees. I really like the community college, because I taught a general biology course, so it wasn’t people who were majoring in biology and so it made me think, ‘this is all they’re gonna get’. I have to do it right. I used to take them on field trips, and they live here and they have never been, really out anywhere and never seen stuff, so they always like that. I like doing stuff like that. I like going outside and poking at things more. And I think that people who especially aren’t necessarily interested in field biology or interested in biology as a major, really enjoy that as well.